Dr. Ali H. Brivanlou

Ali H. Brivanlou, Ph.D.

Robert and Harriet Heilbrunn Professor

Laboratory of Stem Cell Biology and Molecular Embryology

Dr. Brivanlou received his doctoral degree in 1990 from the University of California, Berkeley. He joined Rockefeller in 1994 as assistant professor after postdoctoral work in Douglas Melton’s lab at Harvard University. Among his many awards are the Irma T. Hirschl/ Monique Weill-Caulier Trusts Career Scientist Award, the Searle Scholar Award, the James A. Shannon Director’s Award from the NIH and the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers.

The Brivanlou laboratory has demonstrated that the TGF-β pathway plays a central role in inductive interactions leading to the establishment of different neural fates, which begins by the specification of the brain. Subsequent work in vertebrate model systems has irrevocably established the pivotal role of these morphogens in the formation of specialized tissues in the embryo. In studies of frog (Xenopus laevis) embryos, Dr. Brivanlou has made several influential discoveries, including the finding that all embryonic cells will develop into nerve cells unless they receive signals directing them toward another fate. A concept, coined “the default model” of neural induction, postulates that neural fate determination requires the inhibition of an inhibitory signal. His laboratory has contributed to the molecular and biochemical understanding of the TGF-β signaling pathway and cross talk with other signaling networks, using comparative studies of frog and mouse embryos and mammalian cell culture. The work has led to the discovery of the molecular basis of epidermal, neural crest and sensory placodes and neural induction in comparative platforms.

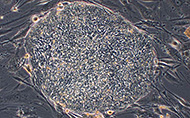

Information obtained from this work provides a strong foundation for research involving hESCs. To address whether the default model of neural induction is conserved from amphibians to mammals (and humans in particular), Dr. Brivanlou’s laboratory was among the first to work directly in hESCs. With private support from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, Dr. Brivanlou and colleagues derived several hESC lines, called RUES1, 2 and 3 (Rockefeller University Embryonic Stem Cell Lines 1, 2 and 3). Using other private funds, his group established an in vivo platform to study hESCs by demonstrating that the RUES1 cells integrate into the mouse embryo, migrate to the inner cell mass when put in close contact and divide and differentiate alongside their mouse counterparts, suggesting that the speed of differentiation of human cells can be reprogrammed to match the mouse. The RUES lines were among the first 13 hESC lines approved for use in research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), under the NIH Guidelines for Human Stem Cell Research adopted in July 2009 under the Obama administration. In this context, the group has also recently developed new tools to perform reversible transgenesis in human and rhesus monkey embryonic cell lines, expressing a variety of reporter constructs controlled by germ layer and tissue-specific regulatory elements. Their current work focuses on the molecular dissection of the defining properties of ESCs — their capacity for self-renewal and their ability to differentiate into a range of cell types.

The Brivanlou laboratory’s overall goal is to use hESCs to study early human embryonic development. Several collaborations with Rockefeller University physics laboratories have also provided new insight, from the use of quantum dots for in vivo embryonic imaging (with Albert J. Libchaber) to development of new statistical tools for DNA microarray and high throughput proteomic analysis (with Marcelo O. Magnasco). An ongoing collaboration with Rockefeller’s Eric D. Siggia focuses on using a high throughput microfluidic platform to program hESC differentiation toward specific fates by dynamic changes of the signaling landscape and without compromising genetic integrity. Thus, the first steps of stem cell differentiation are being scrutinized using new high-resolution techniques drawn from physics. This data will be organized and developed into a predictive tool to rationally reprogram specialized fates from hESCs.